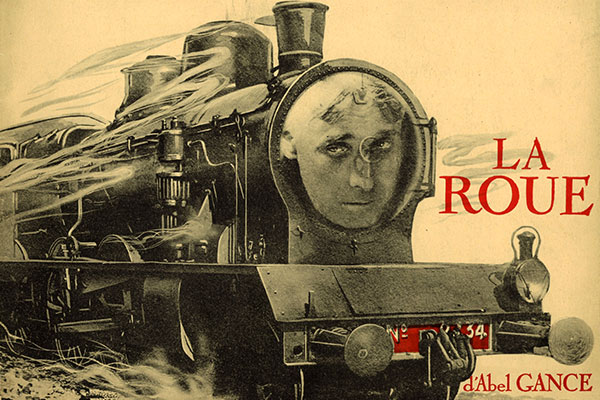

The Wheel

The interminable saga by Abel Gance

POSTED ON OCTOBER 12, 2019

Sisif, a railway worker and single father of a boy, takes in a girl he has just saved from a railway disaster. Years later, when she turns into a pretty young woman named Norma, her adoptive father, who always hid the fact that she was adopted, falls in love with her. Raised in the modest and bustling railway environment, Norma does not understand why her father is suddenly distant, and worse, wants to marry her off to a rich man. Believing she is helping her family, the young woman resolves to marry a person she does not love. The object of her amorous affection is none other than her adoptive brother, and the feeling is mutual. Such is the completely crazy postulate of The Wheel, an endless saga by Abel Gance (1923).

It is a love story that is bewildering, impossible, unjustifiable, developed in the heart of an abounding world, where everything reacts: people, of course, but also consoling animals, vibrating plants, objects as witnesses. More than a social commentary that it depicts on the condition of blue-collar workers or the lifestyle of the high bourgeoisie, The Wheel is above all an emancipated film, filled with a nearly spiritual elevation. Rather spectacular power takes them to the summit of Mont Blanc and the protagonists advance without ever stopping to fulfill their destiny.

The Wheel is obviously also the wheel of fate, and nothing and no one will be spared in what Gance referred to as the catastrophe of feelings. Visually stunning with its pitch-black night scenes, fantastic superimpositions, talking locomotives, its unbridled frenzy that eventually results in rape, The Wheel shows how difficult it is to be "human" being before being a man or woman, in the formatted sense that society imposes. Finally, it is a grand film about the courage it takes to continue living when you expect nothing more from life and complaining seems absurd.

Virginie Apiou