Bellocchio in three revealing films

Posted on OCTOBER 15 AT 12PM

The Bellocchio universe places itself at the heart of the family: either in the intimate circle, or the more collective one, the people of a country, Italy.

A world with dark-ringed eyes

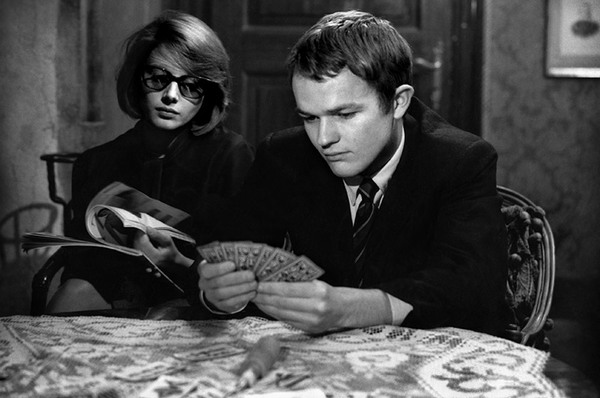

Marco Bellocchio’s cinema is a subversive song emerging in a first film, Fists in the Pocket (1965), revealing the filmmaker as the great poet of family neurosis, one that thrives in interiors devoured by a thick bourgeoisie. In Fists in the Pocket, the heroes with bags under their eyes and pasty white skin can no longer bear to take refuge in the hollow of gaunt pillows inside poorly ventilated rooms. With a unique eye for detail, Bellocchio develops a sensory cinema of touch in the midst of a family cursed with a degenerate atavism. One gently bites a man’s covered shoulder, one wakes out of slumber a young and entangled body, like so many gestures failing in their salvation. And suddenly, the young yet faded heroes of the film thrash about in a fantastical hunting scene, because Bellocchio had the genius idea to shoot it at night, like a startling ceremony, where family life becomes a fight to the death.

A world of prodigies

Bellocchio’s interest in family leads him to question the collective interiority of the Italian people. From it, he retains the traumas: the 1978 murder of Aldo Moro in Good Morning, Night (2003), the advent of Mussolini in 1915 with Vincere (2009). Obsessed by the organic aspect of things, the filmmaker thwarts the clichés of the historical genre by rendering the Italian psyche through the eyes of the women involved: Ida Dasler, Il Duce’s secret wife and Chiara, a terrorist of the Red Brigades. Through these feminine eyes, men reveal their true power. The power is moral when Moro, then a prisoner, tells his executioners: “I must find the word that goes straight to the heart. There is only one. Not two.” The power is vile when it comes to Mussolini hammering his speeches. And here again, he touches on the ceremonial of a people inhabited by religion and politics, marching towards fascism, or of astounded Italians witnessing an open elevator bearing the anarchic symbol of the Red Brigades, traced in blood. The films of the highly inspired Bellocchio exorcise this world of nightmares enshrouded in music and disturbing vibrations by immersing themselves in it as if it were an immense adventure.

Virginie Apiou